March 26: The Six Cello Suites (BWV 1007-1012); Mstislav Rostropovich, cello.

In which Bach invents metal?

The cello suites! Bach likely wrote these for students and, in his crowning way, bestowed music for the ages. These works are so versatile. They reward close and repeated listening. They are touchstones for pedagogical study. Or they can just as well serve as appropriate background music to your zhuzhed-up brunch.

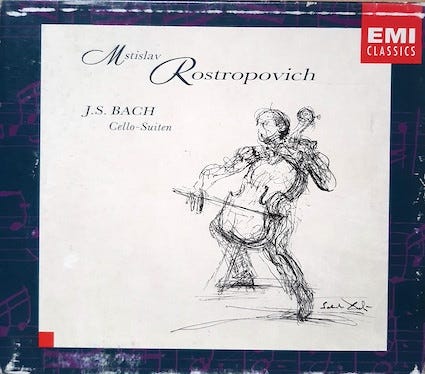

I’ve loved these pieces since I ordered the Mstislav Rostropovich 1991 double-CD set from the BMG Music Club when I was in college. (Side story: I spent a fascinating hour with the CEO of that club two decades after its collapse. He told me he had amassed a collection of over 10,000 CD’s. I asked him what happened to it, given Spotify and whatnot. He yanked his thumb over his shoulder, and made a sound like phwwwit.)

I was lucky to see Rostropovich conduct the New York Philharmonic in 2006 for two giant works by his teacher Shostakovich. The small man had an immense presence, imperious, maybe dickish, but completely in command of the orchestra and the scores. Late seaters filed in after the first movement ended. Rostropovich turned from the podium and just stared at the audience for two minutes in exasperation before getting back to business. Intense!

It’s been so much fun to dig into these pieces again for this post. Rostropovich’s recording is reverb heavy, full of grace and attained glory — he knows exactly how good he is without playing too cocky or too cute. With a meaty tone and wide dynamic range, he plays with supreme confidence. These aren’t the most emotionally resonant performances, perhaps even a bit brainy, but they are wonderful. (There is video of Rostropovich playing the suites in 1991 on Youtube. (Also: Spotify, Apple Music.)

These are the first masterpieces written for solo cello. Bach intuited the challenge: in pieces for single note instruments, you must establish a chordal home to develop the harmony, but this can never be at the expense of the melody or you risk boring the listeners. The converse is also fraught: too much melody without a defined harmonic center can feel wandering or noodly.

Bach decides to win every which way. He intersperses two- and three-note chords throughout for grounding. He periodically checks in to remind us where the harmony and downbeats are, but he’s never afraid to subvert our expectations. Some of Bach’s greatest melodies are tucked into these suites, many of which are used to establish those chordal centers. He’ll build tension with a single line and pedal tones, but always release it.

Those are the ingredients of a masterpiece. Here are highlights from two of the greatest hours of composed music, works that have inspired millions of cumulative hours of study from professionals and amateurs who get to hone their craft in the company of genius.

I can’t not quote one of the most all time famous bits of music, the prelude of Suite No. 1 in G Major, with the intro followed by the famous climbing ending:

Listen how he increases his volume the tiniest bit just before he releases the last chord:

The second movement of Suite No. 1 has an incredible opening chord:

Many of my favorite movements in the suites are the final Gigue dances — I think they’re particularly memorable for following so much development to deliver a kick. Here’s the Gigue to Suite No. 1:

Buckle up for the opening chord in Suite No. 2, Movement 3:

The kick Gigue of Suite No. 2 has a great riff with drone note:

My friend Dasha and I once spoke about how our favorite melodies are often the most simple. We sang a bit from a Tchaikovsky ballet that was just a major scale moving down step by step for an octave. Couldn’t be simpler, still a great song.

Suite No. 3 starts with a scale, and a few minutes later minutes Bach delivers a variation of it for of my favorite licks of all time. The Allemande starts with a perfect melody — easy to sing, easy to remember, catchy, not so easy to compose that I’d have ever stumbled on it myself. Then, Bach gives us a double-stop section with a climbing melody, turning the main phrase inside and out. So great. Rostropovich plays the Allemande jauntily, but this movement works moody, too.

The Prelude appetizer:

The Allemande main. Sing the first four seconds on repeat until you’re sick of it:

And the kicker Gigue from Suite No. 3. Eight seconds into this clip is sort of metal:

Rostropovich shows off his delicacy in the sixth movement of Suite No. 4:

Sometimes these suites are programmed as ‘Evens’ and ‘Odds’. I’m an Odds guy (and, often, an odd guy). The last of the Odds opens with big minor chords. The cello sounds huge, reaching way down for the lowest notes. (There’s a little cheating here — the lowest string is tuned down a step which allows for the massive low G’s.):

The fifth movement of Suite No. 5 is one of my favorites. Rostropovich is nimble and sometimes a little cheeky with his bow:

We’ll conclude with the weirdest moments in the suites, both of which are from the opening movement to Suite No. 6. There’s almost no other harmonic strangeness in any other part of of the suites. Maybe Bach was in a mood that day.

About a minute in to the piece, Bach lays down some out-of-tune calls and response:

And the ending’s spooky overtones glide into an ending without conflict:

These suites are just magnificent. Perhaps my favorite Bach — the lone voice just speaks to me. (In the early days of the pandemic, this was the only music I could listen to.)

The Netherlands Bach Ensemble produced an incredible series of videos with each suite performed by a different cellist. Definitely check out the Sixth Suite — played on the five-stringed shoulder cello Bach may have had in mind for that final suite.

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLecKPCyj4yROEWW268aqNqgeo0tiehjZf&si=NnzjNOwqf4yzN-yd

I just happened to google "Rostropovitch talking about the cello suites" and this came up! Which I hadn't read before. Great essay Evan, hope you're well.