April 2: Cantatas (BWV 26, 60, 70, 80, 106, 116, 130, 140); Münchener Bach-Orchester; Karl Richter, conductor.

On getting spooked at temple. (Perhaps, for you, at church).

Life is strange and inexplicable, and religions are systems we’ve created to help us manage its triumphs and tragedies. What should we do when people are born, or reach adulthood, or die? Can we explain why people whom we love suffer? Are there any consolations in this life, or (as Paul Simon recently sang) is it merely two billion heartbeats and out, waving the flag in the last parade?

As a boy, I regularly attended my family’s conservative Jewish temple in New Jersey. The one prayer that gave me an annual spook was the “Unetanneh Tokef”:

On Rosh Hashanah it will be inscribed and on Yom Kippur it will be sealed:

how many will pass from the earth and how many will be created;

who will live and who will die;

who will die after a long life and who before his time;

who by water and who by fire, who by sword and who by beast,

who by famine and who by thirst,

who by upheaval and who by plague…

But Repentance, Prayer, and Charity mitigate the severity of the Decree.

It’s all been pre-planned by the Holy One, but we have some sway through our behavior? It’s absurd, maddening, and, yeah fine, motivating.

Then the cantor would blow the shofar, its piercing, clarion blasts shattering the air and commanding total attention. Silence would briefly reign — a sorrowful, unnerving, communal truth — before the congregation would resume its sotto voce Hebrew mumbling. This ‘worked’; I was reliably shaken.

Mostly it stirred memories of my late grandfather, whose absence I had trouble integrating into my life. I was just a little kid struggling in middle school, sad in the knowledge that Moishe was the first of all the people I loved who would one day just disappear, and live only in memory.

J.S. Bach was a deeply religious man, and much of his music is inextricable from his faith. Just like the rabbis did with the “Unetanneh Tokef” prayer, Bach composed many hours of music to stir the cores of his fellow churchgoers. He reminds us that an all-powerful, loving, but unpredictable and demanding God is ever present.

So it is in the sacred Cantata BWV 70 Wachet! betet! betet! wachet!, which opens with these lines:

Watch! Pray! Pray! Watch!

Be ready at all times

until the lord of glory

makes an end of this world…

Be frightened, you impenitent sinners!

A day is dawning from which no one can hide.

Today’s excerpts are from the second volume of the “Sundays After Trinity” recordings by the Münchener Bach-Orchester conducted by Karl Richter on the Archiv label, recorded between 1959 to 1979. (Apple Music; Youtube; Spotify I couldn’t find, but search the platform by BMV for plenty of choices.) (Here’s my post on other cantatas from this recording.)

In the third movement of BWV 70, Bach scores the lines

Wake up, you souls, out of your complacency

and believe, this is the last time!

in a low register, with strings and organ and an alto voice:

The intro to the fifth movement is a dense little gem. It starts surprisingly on the third beat, with the organ starting its little scale melody, then the strings come in with a jabbing melody in minor that turns to major, sort of leaving the organ to do its own thing. Then every part plays its own scale melodies and the jabby part recapitulates. Edith Mathis is the soprano:

Hop on the train for the ninth movement, your conductor is Diedrich Fischer-Dieskau, your destination is Armageddon:

In the next movement we get to a happier place, where

Jesus leads me to calm,

to the place where there is fullness of delight.

Listen for Fischer-Dieskau’s falsetto, dropping down to an extraordinary low note and right back into falsetto. Incredible singing here.

Five stars for this cantata, Bach had a lot to say in this one.

Here are some highlights from the rest of this recording:

The opening of BWV 60 is an off to the races moment. This vibe feels predictive of the orchestrations of Haydn and his buddy Mozart:

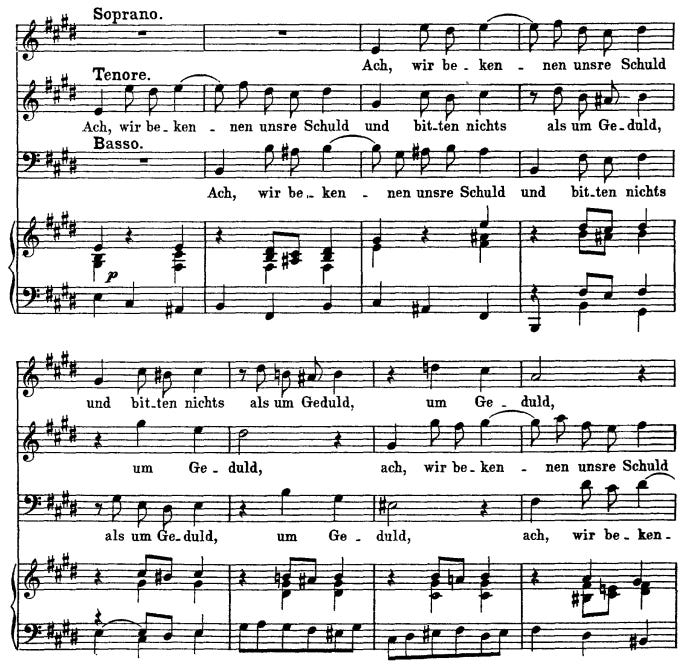

In the fourth movement of BWV 116 there’s a pseudo-canon vocal trio, with a murderer’s row of singers: Schreier, Mathis, and Fischer-Dieskau. Here’s the opening with the score:

And when they pivot to the minor key:

Dramatic strings support the singer in the fifth movement of BWV 116:

In the opening movement of BWV 26, Richter almost loses control of the orchestra. There’s a punchy scale lick that first goes up then down, and is iterated throughout the entire cantata. This movement might be star of the show for me this week.

The flutes and strings are more successful than the vocals in the tricky scale work of Movement Two:

There are lots of intertwining parts swirling into the end the opening movement of BWV 80; I’m not sure if this excerpt will be satisfying, outside of what led up to it:

In the third movement of BVW 130, it sounds like the basso Fischer-Dieskau is singing about “glorious light,” which fits with this religious theme, except oops I listen in English and I’m thinking with the wrong ears:

What the German auf neues Leid actually translates to is, “bring new pain.” Yeesh. (For the record, my son has piped in to say that the opening line sounds like, “Ach, I play Fortnite.”)

My promise to you: after St. Matthew’s Passion and this collection, I’m going to cover some lighter music for my next post. See you soon.